|

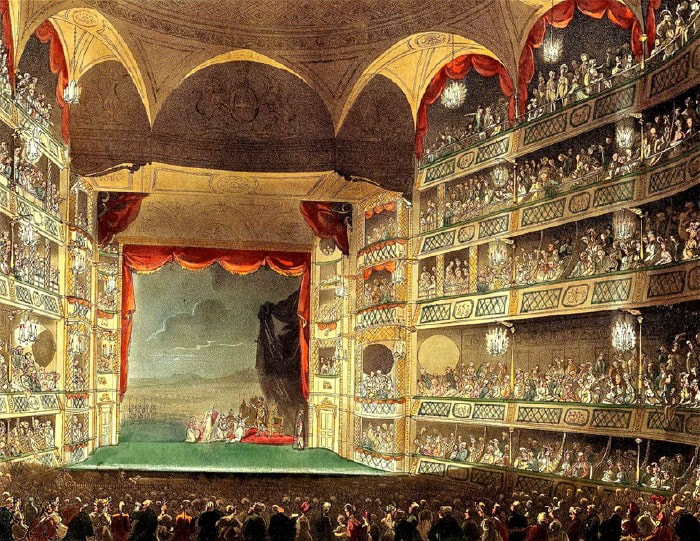

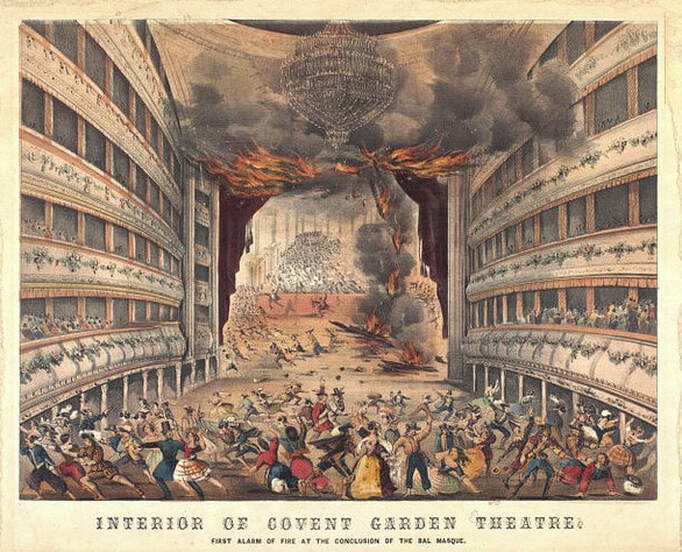

Hooray, 2020 is nearly over, and things are already looking up for 2021 – Donald Trump is out of the White House, and there are several potential COVID vaccines in the making. For me, 2020 has been a particularly eventful year: I got a job; I lost a job (blame the coronavirus); I moved back in with my parents; I started this blog, and my long-term partner broke up with me. This year’s Christmas and the New Year will be one to remember too, if only because of the effects of the health crisis. My guess is that there will be a lot of Zoom-ing and Skype-ing over the Christmas period and online shopping platforms will make a roaring profit. One of the things I will miss this year is a visit to the pantomime. Admittedly, it was always too loud and difficult to negotiate the crowded auditorium with my dodgy balance. Still, it is easy to underestimate the power of a good laugh in the company of friends and family, and hey, what are earplugs for? I know I’m lucky. I can walk through the main auditorium, despite the difficulties, and can only imagine how difficult it must be for those less mobile than myself. All modern theatres should have provisions, by law, for the physically disabled – ramps, wider doors and particular seating areas in auditoria. But this is not always possible to achieve when renovating older theatres, no matter how hard an architect might try. I have this on the authority of a theatre architect. Said architect, Mark Foley, from Burrell Foley Fischer LLP, told me that eighteenth and nineteenth-century theatre spaces can be tough to adapt because of the way historic theatres were built. Visitors to cities wanted entertainment, which during these centuries equated with a visit to the theatre. Thus savvy businessmen spotted an excellent investment opportunity. But, in order to pack in as many people as possible, the buildings had large auditoriums with narrow, steeply raked seats; small (or non-existent) foyer spaces; steep staircases and narrow exits. It can be challenging for contemporary architects to alter these without compromising the structural integrity of the building or sightlines. In the past, theatres were also a huge fire risk. The oldest theatres, Shakespeare’s Globe, for example, were wooden constructions and the interiors of Victorian theatres contained a great deal of wood too. Add to this the heat of several thousand bodies, not to mention the flames from the limelights, and theatres were accidents waiting to happen. Nearly every theatre burnt down at least once: Drury Lane in 1672 and 1809, Covent Garden in 1808 and 1856, the Lyceum in 1830, the Garrick in 1846, Edinburgh’s Theatre Royal in 1865, Cardiff’s Theatre Royal in 1877 and many more across the world.

Fatalities were common. Many people died from smoke inhalation or were crushed to death in the panic to escape. One of the worst nineteenth-century theatre fires in Britain was at the Theatre Royal in Exeter in 1887, when 186 people were killed. This was far from the worst – more than 600 people died in the Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago in 1903. All this makes it very challenging for modern-day architects to redesign the theatres to comply with current health and safety standards and disabled access legislation. Many of these buildings are listed, meaning there are limits to the alterations that can be made. “It’s a real challenge and, in fact, if you’re starting from scratch it’s much easier. When you first begin a contemporary theatre venue, you might allow .75 square metres of floor area in the foyer for every person that you have in the auditorium. In a Victorian theatre, a lot of them didn’t have any floor space [in the foyer] at all,” said Mark. Surprisingly, when renovating an old theatre, Mark told me that the first thing architects consider is how to fit in a heating and ventilation system. When he explained the reasons why it did make sense. Georgian and Victorian theatres heated up quickly and had crude ventilation systems which, ironically, often trapped smoke inside – definitely a health and safety concern for modern-day people. Only when this has been planned out, do architects consider how to adapt stage space, auditoria and foyer areas with the appropriate provisions for the disabled. What results is a smaller auditorium with wider seats and a larger foyer. Yet, it is impossible to cater to every person’s individual disabilities, so what ends up is a compromise which hopefully still allows everyone to have a pleasant experience. As Mark said: “Not everybody can provide a perfect environment, but you can still make it a really pleasurable experience, just by how you manage. That that is absolutely critical as well.” So, the next time I’m at an old theatre and I fall down because some pushy person has knocked into me (it has happened), I will not blame today’s architects. Instead, I will blame eighteenth and nineteenth-century theatre designers. Comments are closed.

|

CategoriesArchives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed